How Many New Jobs Would the National Infrastructure Bank Create

and

How Much Would They Pay?

by Alphecca Muttardy Last Updated April 21, 2020

The following article was written in response to questions about the functioning of a proposed National Infrastructure Bank (NIB), which is being discussed around the county and on Capitol Hill. Mrs. Muttardy, a macro-economist and 25-year veteran of the IMF, is a leading spokeswoman for the Coalition for a National Infrastructure Bank promoting and educating citizens for the bank proposal.

One great question is how many new jobs will be created by $4 trillion in additional spending on infrastructure, and how might those new jobs change employment and pay levels over time? Regarding the count of jobs, there are a number of estimates of new jobs created from increased infrastructure spending (all estimates prorated to a common level of $100 billion in spending):

- The Federal Highway Administration estimated that every $100 billion invested in the nation’s highways supports 2.8 million jobs, of which 34% would go to on-site construction jobs, 16% to supplier industries, and the remaining 26% of jobs throughout the rest of the economy.

- The Council of Economic Advisers estimated in 2011 that every $100 billion in infrastructure investment creates about 1.3 million new jobs. Their estimate was used by Democrats, who put forward a $1 trillion infrastructure plan in 2018.

- • The Economic Policy Institute (EPI), in their 2017 study of all economic benefits from infrastructure investment, concluded that each $100 billion in infrastructure spending would boost job growth by 1 million full-time equivalent jobs.

The reasons for differences in the above estimates?

First, the year the study was done matters, because infrastructure costs are doubling every 10 years, (largely on account of rising costs for construction materials, and inefficiencies in project management, government contracting, and regulation).

Second, not all new money can be spent at once, but needs to be phased over time. Accordingly, workers might move from one new project to another that is scheduled later.

Using the most conservative EPI study above implies that $4 trillion in spending would support 40 million full-time equivalent jobs. However, if the $4 trillion is spent over 15 years, and each project requires a person (engineer, electrician, road crewman, etc.) on the job for an average of 2.7 years, then a minimum of 25 million workers might be needed over time to rotate in and out of the new jobs that the NIB creates.

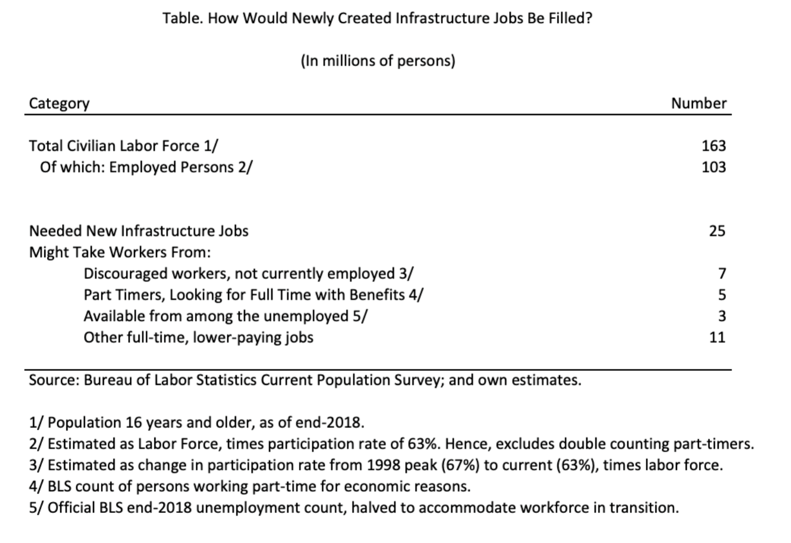

Worker Supply as of End-2018

So, where would the 25 million workers to fill these new jobs come from? Using end-2018 data, we had estimated that roughly half might be eligible workers who are currently discouraged by low wages or the unavailability of full-time jobs in their area (see Table below). And the remainder might come from those already in the workforce who switch over to infrastructure jobs for reasons of: higher pay, stable employment, and benefits. The NIB proposal would look to labor unions, trade schools, and colleges to train all of these new workers.

The Coronavirus Recession

However, today, the United States has 22 million people unemployed

as a result of shutting down so many businesses to combat the spread of the coronavirus. Whether or not job losses become permanent

(i.e., the Recession is V-shaped or L-shaped) will depend on: how adequate and well-targeted government relief programs are at preventing another financial crisis, and how fast an effective vaccine can be deployed so that businesses can safely re-open again.

Clearly, the National Infrastructure Bank has an important role to play in fighting the economic effects of the COVID-19-induced Recession to ensure that it is V-shaped.

To firm up our job creation estimates, we are currently seeking a statistical projection of the NIB’s effect on the entire economy under today’s employment conditions, similar to one that was done in 2014

by the University of Maryland using their INFORUM Model.

Wages

Finally, what might the new jobs mean for wages, especially since the scale of the National Infrastructure Bank is so large? On one level, there will be significant demand for workers that will bid up all occupational wage levels. Also, construction contracts financed under the NIB would require that workers are paid union-level, Davis-Bacon Wages. At the same time, GDP growth is expected to recover and rise sharply, as infrastructure investments lead to greater productivity gains, and an increase in private sector investment. Both of those developments would mean that price levels, overall, are likely to remain unchanged.

History suggests that substantial wage compression – pushing all occupational wage levels from the bottom upwards – would be the fundamental outcome. In their book, Unequal Gains, Professors Lindert and Williamson investigate the underlying causes of The Great Leveling, the period from 1900-1970

when income inequality fell sharply. They conclude that “market fundamentals … could have pushed the entire occupational wage structure toward equality even in the absence of changes in government wage-setting policies [like the Minimum Wage].” Their conclusion is echoed by occupational wage data. During the period 1933-1957,

when FDR’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation

was financing lots of infrastructure projects that hired lots of workers, the pay of unskilled workers

rose by nearly 400 percent (well above the Minimum Wage, first set in 1938).

Thus, for now, we anticipate that the operations of the NIB will create 25 million full-time jobs, cumulatively over 15 years, will re-employ those Americans whose lose their jobs on account of the current COVID-19 Recession, and in addition will stimulate wage recovery for many, if not most, Americans.