Response to Bond Market Questions and the Need for a National Infrastructure Bank

September 19, 2023

This document responds to questions raised by interested parties as to whether or not a $5 trillion National Infrastructure Bank (NIB) is actually necessary to finance our nation’s public infrastructure. The questions appear to center around two major topics:

1. Can’t municipal bond markets cover U.S. infrastructure needs? Why is a National Infrastructure Bank Needed? And,

2. Should local governments raise debt levels further through borrowing from the National Infrastructure Bank?

After laying out the scope of infrastructure financing needs, these two sets of questions are answered in turn below:

Scope of Infrastructure Financing Needs

Q: Who owns and finances public infrastructure?

A: According to the definition used by the Bureau of Economic Affairs, in 2017 the Federal government owned $.782 trillion (7%) of non-defense public assets (mostly public housing and AMTRAK), while state and local governments, and municipal authorities (SLGMAs) owned $10.6 trillion (93%) in public assets (roads, bridges, mass transit systems, water utilities, schools, parks, etc.).[1] Meanwhile, SLGMAs accounted for 75% of spending on infrastructure capital and maintenance improvements in 2004, compared with 25% by the Federal government.

Q: How do states finance infrastructure improvements?

A: States pay for public buildings, facilities, roads, and other infrastructure somewhat differently than they fund other types of spending. For example, they use debt more frequently and often rely on user fees like tolls, or gas or sales taxes, to fund infrastructure. In addition, the federal government provides grants for roads, transit, and other infrastructure, but federal grants often require 20% matching funds. Accordingly, state revenues are required, regardless of the funding method that’s used.

Borrowing: There are sound reasons why states and localities borrow to pay for infrastructure rather than use annual tax collections and other revenues to “pay as you go”. Public buildings, roads, and bridges are used for decades but entail large upfront costs; borrowing enables the state to spread out those costs and repay over time. As a result, taxpayers who will use the infrastructure in the future help pay for it, which promotes intergenerational equity. Borrowing also makes infrastructure projects more affordable by reducing the pressure on a state’s budget in any given year. On average, states finance 27 percent of their capital spending with bond proceeds.[2]

[1]

It’s Time for States to Invest in Infrastructure, By Elizabeth McNichol (Center for Budget and Policy Priorities), March 19, 2019.

Q: What is the current need – and financing gap – for infrastructure?

A: The 2021 report card of the American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that infrastructure needs $6.1 trillion over 10 years (expressed in 2019 dollars) to bring it up to a state of good repair.[1] Of that amount, Federal, state, and local governments and the municipal bond market are expected to contribute $3.5 trillion (27% from municipal bonds). However, a financing gap of $2.6 trillion remains. Every year that the financing gap persists, maintenance and construction costs will add on another $3-500 billion on to the final bill. Moreover, the gap does not include what is needed to build High Speed Rail, water management systems to address drought and ensure adequate food supplies, renewable energy grid expansion, or affordable housing. Adding these categories will require $5 trillion in new money over 10 years, to complement existing spending and finance all of our country’s needs.

Meanwhile, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, IIJA) provides only $550 billion in new money to address the current financing gap. It covers only 1/10th of what is actually needed. Further, the Act requires grant recipients to contribute matching funds, ranging from 10% to 75% of the total project cost, that may have to be borrowed.[2] And, more than half of funds are only available through competitive bidding, for which local agencies may not have the manpower or capacity to compete.

[1]

2021 Failure to Act: Economic Impacts of Status Quo Investment Across Infrastructure Systems, American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

[2] Muni Bonds Gear Up to Support City Infrastructure Investments, by Mike Stanton, Communications Director for Build America Mutual, August 15, 2022.

The Municipal Bond Market

Q: What is the current size of the Municipal Bond Market?

A: As of QII 2022, outstanding balances in the U.S. Municipal Bond Market totaled $4.04 trillion.[1] Of the total outstanding, about $1.23 trillion is owed by state governments – i.e., the debt is on the books of state governments for the infrastructure they own.[2] The remaining 70% of bonds outstanding is owed by counties, cities, utilities, and municipal authorities (transit, housing, etc.), for the infrastructure they own. Each bond issued by a government entity has its own specific credit/bond rating.

Q: What are current earned yields and maturities for Municipal Bonds?

A: As of October 2022, the current average yield on municipal bonds – before tax incentives -- was 4.0 % per annum, [3] while the average maturity on new issues was 19 years.[4] That roughly equals the 20-year Treasury bond yield (of 4.0% on Oct. 3, 2022),[5] which is the rate the National Infrastructure Bank would charge for an infrastructure loan of that maturity. Unlike the stock market, there is no publicly searchable daily price information for municipal bonds. Muni borrowers and investors typically rely on the dealers in the middle of each trade—buying bonds from a government or an investor and selling them to another investor—like the data provided by SIFMA—to propose prices for the securities.[6]

Q: Who issues bonds, and what are the procedures?

A: State and local governments and municipal agencies sell bonds in the roughly $4 trillion municipal market to finance infrastructure such as roads, sewers and high schools. Before offering a new bond for sale, the issuer may need to seek voter approval if repayments will come out of general tax revenues (called General Obligation Bonds). Even where repayments are assured by a given stream of money (e.g., user fees, or special taxes; called Revenue Bonds that do not require voter approval), bond issuance may be limited by laws that constrict all debt service payments as a percentage of all revenues. In a few states, there are constitutional amendments against taking on any debt, although states can still issue debt through a legally separate “component unit” to overcome those limits.[7] In the main, issuers need to work with at least one Credit Rating Agency to obtain a credit rating for the bond.[8] Other things being equal, a better bond rating translates into lower financing costs. Finally, issuers can organize themselves through a Bond Bank,[9] an independent state-created entity that consolidates local bond issues into a single pool to offer better financing options for state or municipal projects.

Q: Who buys bonds, and what are the procedures?

A: Ultimately, most municipal bonds are bought by households, either directly or through mutual or exchange-traded funds. Interest earnings are typically exempt from federal and often state taxes, attracting high net worth individual investors. Before the final purchase, however, broker-dealers and investment banks buy the bonds from a government or an investor and sell them to another investor for a marked-up price (and slightly lower yield). A recent study[10] found that that resales by dealers have raised bond prices by 1-2%, despite regulations that are supposed to protect end-customers against high service fees. A dealer might also combine bonds issued in a given state, so that buyers can take advantage of tax exemptions in that state. The 2022 WSJ report corroborates a 2019 study that found that customers who bought newly issued bonds were immediately turning around and reselling them to dealers for higher prices than the original government issuer got, often reselling them back to the banks initially hired to price and underwrite the bonds. The five largest dealers in the municipal market, by volume of new debt underwritten, are Bank of America Corp., JPMorgan Chase & Co., RBC Capital Markets, Morgan Stanley and Citigroup Inc.

Q: Has the municipal bond market grown in line with infrastructure financing needs?

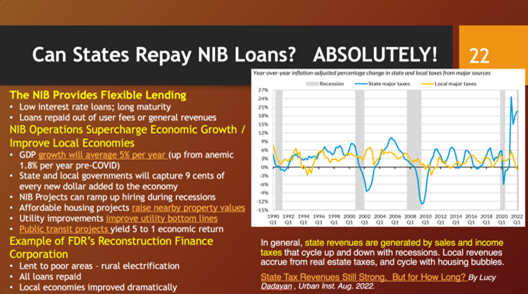

A: No. In 2017, Municipal Bonds outstanding were $3.93 trillion, nearly the same level as they are today. Meanwhile the 10-year financing gap for infrastructure has grown from $2.1 trillion reported in the 2017 ASCE Report Card, to $2.6 trillion in the 2021 Report Card. Municipal bonds have not expanded to fill this finance this gap. Deteriorating state finances are not to blame: muni bonds are a high quality asset class, 85% of them carrying an A bond rating or better. And state finances have improved markedly to support borrowings (see Slide 22 below). [11] Looking forward, escalating economic growth, coming from NIB operations, will raise revenues further, and partly offset any borrowing-as-a-percent-of-revenue limitation. Finally, liquidity in the banking system (capacity to lend) was very high, and demand from borrowers very high,[12] but that did not translate into more bond issues either. The only possible conclusion is that Wall Street Banks would rather pour money into riskier investments providing higher yields (like corporate junk bonds), than finance more public infrastructure projects.

Q: From the perspective of government entities seeking infrastructure financing, what are the disadvantages of municipal bonds?

A: The following disadvantages of “muni’s” were identified by agencies who organize bond issues for their respective government clients:

· There are a lot of strings attached to getting a good bond rating from a Credit Rating Agency. State bond banks typically have to combine bond requests from poor and well-off neighborhoods in order to get a better rating. The market has an estimated 35,000 different borrowers, according to research firm Municipal Market Analytics, and debt is often sold in small increments, so organizing financial information about all these government components involves a lot of administrative work.

· Related to bond bundling, communities often do not have a concrete database or pipeline of infrastructure projects in need of funding, or timetables and cost estimates for the projects. Lining up just 10 projects in 10 communities can also entail a lot of coordinating work.

· The bond market is relatively inflexible, with standard bond terms for the next twenty years, and no options for renegotiation.

· There is a lot of concentration in bond underwriting, which drives up the costs of issuing bonds. 85% of bonds are handled by just 6 broker-dealers. High service fees suggest the cost of underwriting is not providing value for money.

Q: What would be the advantage of a city or a county borrowing from the National Infrastructure Bank (NIB) instead? Why can't the bond market meet their needs?

A: Municipal bond markets are simply not adequate to meet the needs of cities or counties to finance infrastructure (see analysis above). NIB lending, by comparison, would complement and top up standard “muni” lending, not replace it, and in addition provides the following advantages:

· Charges low interest (Treasury bond rate) with long maturities (matching the investment’s lifetime), with flexible repayment terms (either out of user fees, dedicated revenues, or general obligation revenues).

· Provides a permanent, long-term source of financing, which infrastructure requires.

· Actively mobilizes financing of projects, especially ones that have been on priority lists for years and have not received funding.

· Provides technical assistance to municipalities (without service fees), to help them in formulating and managing loans, and bundling projects to lower costs.

· The scale of new lending – $5 trillion over 10 years –dramatically raises economic growth to 5% on average per year on average,[13] accelerating new local revenues that will allow SLGMAs to repay back loans.

· Constitutes a national development bank that can tackle local and cross-border permits, organize regional economic accelerator planning among states, and facilitate reshoring of manufacturing and supply chains.[14]

Q : U.S. infrastructure needs are huge, but what evidence do we have that there is demand for new borrowing? That is, if the city of Providence, RI hasn't already borrowed to replace its lead pipes, why would a new source of debt make that more likely?

A: Demand for new borrowing can be seen in the documented size of the financing gap for infrastructure, and in the lists of projects that request state and local financing, but are repeatedly left out of budgets every year. E.g., cities requesting lead pipe replacement would receive full funding of about $280 billion, to fully complement the $15 billion for lead pipes in the IIJA. Where municipalities decline to replace lines in homeowners’ yards, the NIB could arrange for affordable financing that is added over a long maturity to homeowners’ utility bills. In very low income areas, the NIB could – through its Trust Fund – provide grants rather than low interest loans, as net income earnings of the NIB permit.

Q : Fundamentally, the NIB is a way to dramatically increase the amount of debt carried collectively by the sub-national governments of the US, as well as private interests. What makes it better for us to assume that debt than simply to pressure the federal government to dramatically increase its deficit spending?

A: There is no room left in the Federal budget to add to the national debt, which now totals $31 trillion. And politicians are loath to raise taxes or debt further. In addition, interest rate hikes caused by Fed policy to fight inflation, will likely double interest payments on the debt by 2032, to 3.3% of GDP.[15] The NIB is a work-around to financing infrastructure through the budget, and requires no Federal spending, taxes, or debt. It is designed to attract maximum political support.

Q: Who stands behind the NIB in a financial sense? Would the NIB seek a bond rating?

A: NIB loans are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the Federal government, both on the capitalization and lending sides. The NIB will seek accreditation from the Office of the Controller of the Currency as a deposit, lending bank, and FDIC insurance. The NIB can issue its own bonds, which will be AAA-rated just like Treasury bonds are.

Q: How much of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) model is still usable and which parts do the current team sees as important or valuable.

A: The NIB’s capitalization differs somewhat from the RFC, in that the former is a deposit-lending bank whose loans add to the money supply, while the latter was a revolving fund. In all other respects the two institutions use similar approaches to:

· Identify and promote infrastructure development projects in every geographic location of the country.

· Employ innovative engineering techniques to create efficiencies, standardize operations, and lower construction costs.

· Build large, transformational projects, like electrification, communications, high speed rail, and water mobilization projects.

· Use best management practices, with full transparency, to ensure projects are delivered on time and on budget, with no financial malfeasance.

· Backstop muni operations by sharing/participation in loans.

As an example, when the Public Works Administration (PWA), financed by the RFC, began buying municipal bonds in 1933 to strengthen financial markets, bond rates declined, it was possible for municipal bond sales to rise on their own, and communities turned less and less to PWA to obtain the loan portion of their project costs.[16]

Should local governments raise debt levels further by borrowing from the National Infrastructure Bank?

A second set of questions centered around whether or not state and local governments and municipalities (SLGMA) should increase their borrowings, and the capacity of the National Infrastructure Bank to manage those projects on a sound investment basis. The questions were posed in an article[17] by Charles Mahron, of Strong Towns, a non-profit group that advocates for public investment emphasizing better maintenance of the infrastructure we already have,[18] rather than taking on new, “unaffordable” debt to build new projects that may not provide an adequate return on investment. In general, the stylized questions from his article, and responses to them, indicate that Mr. Mahron’s critique relies on anecdotal evidence, and ignores the broad macroeconomic and historical evidence of the benefits of expanding investments in public infrastructure.

Q: Are there public infrastructure projects out there that are in need of financing and can provide an “actual financial return”? “If those projects existed (and they really don’t anymore), they are easily funded. What cities are actually struggling with isn’t money for expansion but money for maintaining what they already have.”

A: These statements are factually incorrect. According to ASCE (see above), there is a backlog of $2.6 trillion in project needs that have gone unfunded, and much of it (bridges, water infrastructure, schools, the electric grid) is on account of infrastructure having reached the end of its useful engineering lifetime.[19] Also, state and local spending on infrastructure is now at an historical low.[20] Municipal bonds have not stepped in to finance these critical projects (see above). As a consequence, to site just one example, there are 45,000 bridges in America that are rated structurally deficient or in poor condition, 3,300 of them in Pennsylvania alone.[21] One study found that while conditions on state-owned bridges have improved over the past 10 years, all of Pittsburgh’s unsafe city-owned bridges remain in poor condition and are still in need of repair.[22]

[1]

US Municipal Bond Statistics, by Securities Industry and Financial Markets (SIFMA), the leading trade association for broker-dealers, investment banks and asset managers operating in the U.S. and global capital markets.

[2] State Bonded Obligations, 4th Edition, by Jonathan Williams, Lee Schalk, Thomas Savidge & Nick Stark (American Legislative Exchange Council, ALEC), July 21, 2022.

[3] Municipal bonds are in the spotlight. Should they be in your portfolio?, by Paul Jacobson and Chris Seter, Nov 15, 2022.

[4] US Municipal Bond Statistics, IBID.

[5] 20-Year Treasury Chart, by YCharts.

[6] Muni Market Transaction Costs Remain High, Despite Customer Protection Rules, Study Says, By Heather Gillers (WSJ), Aug. 4, 2022.

[7] State Bonded Obligations, 4th Edition, IBID.

[8] Credit Rating Basics for Municipal Bonds on EMMA, i.e., on the Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA®) website and database. In the ratings guides, there will be a rating scale for each bond (e.g., AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, B, CCC, CC, C, or D(Default)), with AAA as the top rating, and any rating above BBB considered as investment grade.

[9] Bond Bank, By James Chen (for Investopedia), Updated November 01, 2022.

[10] Muni Market Transaction Costs Remain High, Despite Customer Protection Rules, Study Says, IBID.

[11] State Tax Revenues Still Strong, But for How Long? By Lucy Dadayan , Urban Inst. Aug. 2022. In general, state revenues are generated by sales and income taxes that cycle up and down with recessions. Local revenues accrue from real estate taxes, and cycle with housing bubbles. And revenues of utilities and transit authorities cycle up and down with the economy and customers’ ability to pay user fees.

[12] ‘Food fight’ in the municipal-bond market as demand devours all supply, by By Andrea Riquier, Last Updated: June 12, 2021.

[13] Catching Up: Greater Focus Needed to Achieve a More Competitive Infrastructure, by Jeffrey Werling and Ronald Horst, for the National Association of Manufacturers, Sept. 1, 2014. The same University of Maryland input-output model was used for all of the 2021 ASCE Failure to Act reports.

[14] On Infrastructure Financing – A national development bank could attract the private capital that America's infrastructure needs, by Terrence Keeley (Global Head of the Official Institutions Group at BlackRock) for American Compass, June 11, 2020.

[15] The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2022 to 2032, Congressional Budget Office, May 2022.

[16] America Builds – The Record of PWA, by the U.S. Public Works Administration, at www.ForgottenBooks.com, pg. 69.

[17] A National Infrastructure Bank is a Stupid Idea, by Charles Marohn, June 14, 2021 (with readers’ comments).

[18] The Strong Towns Approach to Public Investment, by Charles Marohn, September 23, 2019.

[19] “A grade of D refers to infrastructure is in fair to poor condition and mostly below standard, with many elements approaching the end of their service life. A large portion of the system exhibits significant deterioration. Condition and capacity are of serious concern with strong risk of failure.” Executive Summary, 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure, American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

[20] It’s Time for States to Invest in Infrastructure, IBID.

[21] National Bridge Inventory of the Federal Highway Administration.

[22] Pittsburgh's bridges on the brink: City's spans decaying with little help, by Joel Jacobs, Sean D. Hamill, Ed Blazina, Jonathan D. Silver, Feb 13, 2022.

On Pittsburgh’s Swindell Bridge, which runs over Interstate 279, there were so many problems -- heavy rusting, exposed rebar, and falling cement -- that interim inspections were ordered every six months. Would you want to commute over, or under, this bridge every day?

Q: Will broad borrowing and replacement of infrastructure provide an “actual financial return”?

A: Yes. All economic studies,[1] based on broad data sets, show that “that public investment spending does lead to a stimulating effect on private spending components of GDP and has a larger impact on GDP via the multiplier effect than other types of government spending.” Moreover, those positive effects are quite pronounced during an economic downturn. A model from the University of Maryland—used throughout for the 2021 ASCE Report Card—found that every $1 invested in productive infrastructure plows back $3 in new business activity and production, even during times of near full employment. Also, large, sustained investment in infrastructure creates millions of new, great-paying jobs; raises average GDP growth from its historical anemic level of 1.5% per year, to 5% per year on average;[2] and lowers inflation due to added production coming on line.

Q: How will borrowers capture the “financial return,” to ensure infrastructure loans can be repaid?

A: The National Infrastructure Bank will provide flexible loans directly to owners of public infrastructure – states, cities, counties, utilities, municipal authorities – that can be paid back out of: user fees (in the case of a utilities and transit authorities), dedicated revenue streams, like gas or sales taxes, or general revenues. Higher economic growth will stimulate new revenues, of which 9 cents of every dollar is captured in new state and local taxes. Utility improvements also improve utility bottom lines.[3] Public transit projects yield 5 to 1 economic returns, which can be given back to transit authorities along with ongoing subsidies that local governments provide.[4] Meanwhile, the very lowest income-earning municipalities – like Flint MI, Jackson MS, or Newark NJ – can request grants rather than loans, as the NIB builds up its Trust Fund for that purpose.

[1]

The Fiscal Multiplier and Economic Policy Analysis in the United States: Working Paper 2015-02

and

The Congressional Budget Office’s Small-Scale Policy Model: Working Paper 2022-08, Congressional Budget Office. And,

Does Infrastructure Spending Boost the Economy? Economic Brief by By Marios Karabarbounis, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, February 2022, No. 22-04.

[2] Catching Up: Greater Focus Needed to Achieve a More Competitive Infrastructure, by Jeffrey Werling and Ronald Horst, for the National Association of Manufacturers, Sept. 1, 2014. IBID.

[3] How Utilities Can Change Investment Priorities and Instantly Improve their Finances, by Jay Sheehan, September 29, 2016.

[4] Economic Impact Of Public Transportation Investment, by the American Public Transportation Association.

Q: How will the NIB ensure financial prudence in approving loans to ensure their repayment?

A: NIB infrastructure loans are approved by the bank’s Board of Directors in accordance with loan provisions set out in the legislation. The NIB uses the same fiduciary rules as any commercial bank. As a rule, 99% of infrastructure loans are expected to be repaid in full and on time, in particular because SLGMAs want to ensure a continued high bond rating. The NIB’s back-office engineers can assist jurisdictions in planning and expediting loans if needed, while NIB loan officers will check to ensure that projects remain on-time and on-budget. Two examples of successful public banks that operated this way include the 100-year-old Bank of North Dakota, still in existence and highly profitable, and the national Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which ended operations in 1957 after earning huge revenues for governments, with all loans repaid.[1] Here is how the NIB would be managed:

[1]

Why grassroots activists are turning to the wonky world of monetary policy to fight for economic justice, by Pamela Haines, November 1, 2022.

Q: Would the NIB be like the South Carolina Transportation Infrastructure Bank (SCTIB), that has “billions in debt (money the taxpayers are on the hook for) that is off books, and essentially hidden in the balance sheet of what is a horribly insolvent bank. If it were a real bank, the FDIC would have shut it down a long time ago.”

A: Again, there is a lot wrong with this statement. First of all, the SCTIB is scrutinized by Fitch Rating Agency for loan quality, and is not insolvent. Recently, Fitch upgraded the SCTIB's outstanding revenue bonds from 'A' to 'A+', affecting all $1.2 billion of SCTIB’s outstanding debt.[1] Second, South Carolina has been quite prudent[2] in using the SCTIB and added gas taxes to finance transportation projects, but it still has a long way to go. ASCE reports[3] that 11% of bridges are structurally deficient, and the state still needs $24 billion over the next 10 years to cover the backlog of road and mass transit projects, plus much more for airports, dams, and drinking and wastewater systems. Third, South Carolina would in fact profoundly benefit from increased borrowing from the NIB – up to $72 billion over 10 years to cover all of the state’s infrastructure financing gap. Those investments would supercharge economic growth and importantly create 320,000 new great-paying jobs to support industry in the state and reduce poverty and income inequality. And loans can sustainably be repaid.

Conclusion: Mr. Marohn appears to be of the conservative school that preaches: no borrowing for public infrastructure; it must only be appropriated through the budget as and when it can be afforded. But America cannot grow that way, and will surely decline without massive new investments to fix our aging systems. Historically, we invented the idea of national development banks to bolster economic growth, and used them successfully four times before in our nation’s past. Today, other countries, notably China and India use them, and are outpacing us to become the world’s future superpowers.[4] [5]

[1]

Fitch Upgrades $1.2B South Carolina Trans Infra Bank Revs to 'A+'; Revises Outlook to Positive, 08 Jun, 2021.

[2] Moody’s bond rating for the state is AAA: CNBC-America’s Top States for Doing Business, July 13, 2022.

[3] South Carolina 2021 Report Card: D+. From the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

[4] How to Green Our Parched Farmlands and Finance Critical Infrastructure, by Ellen Brown, September 1, 2022.

[5] The US is a waning economic superpower. When will policymakers realize it?, by Seth Benzel and Laurence Kotlikoff, The Hill Opinion Contributors - 11/02/22.